If you were watching closely last Saturday night you might have seen him. He was there in Ian Machado Garry’s corner, whispering in the welterweight’s ear between rounds, chiding him for his risky use of the wrong half-guard in the final round, fine-tuning the already pretty finely tuned points of the fighter’s transition game.

Of course, in order to know who you were looking at and why he still matters so much to mixed martial arts, you’d need to know at least a little bit of the history of this sport.

Advertisement

Or you could also ask Reinier de Ridder, who fights Bo Nickal in the co-main event of Saturday’s UFC Fight Night event in Des Moines, Iowa. Ask him who he looks up to as a submission grappler trying to make that style work for MMA.

“It’s really just one guy, and that’s Demian Maia,” de Ridder told Uncrowned earlier this week. “He’s the guy. You look at what he did, his creativity — he’s the one.”

He’s not the only fighter who feels this way. Years ago I talked to Neil Magny right after he’d been submitted by Maia at UFC 190. He’d gone into the fight knowing that Maia was supposed to be some kind of jiu-jitsu wizard, but so what? He’d fought good submission grapplers before. He’d won seven straight fights in the UFC and was feeling pretty confident.

“I had a great training camp, felt like my coaches had brought in the guys I needed to train with, all that,” Magny told me in 2016. “But then getting in there and experiencing his pressure, I realized, wow, this guy is on another level. … I had kind of got to feeling like I was untouchable, then this guy comes along and exposes me on the ground. I was like, how can I get to the point that he’s at right now?”

Advertisement

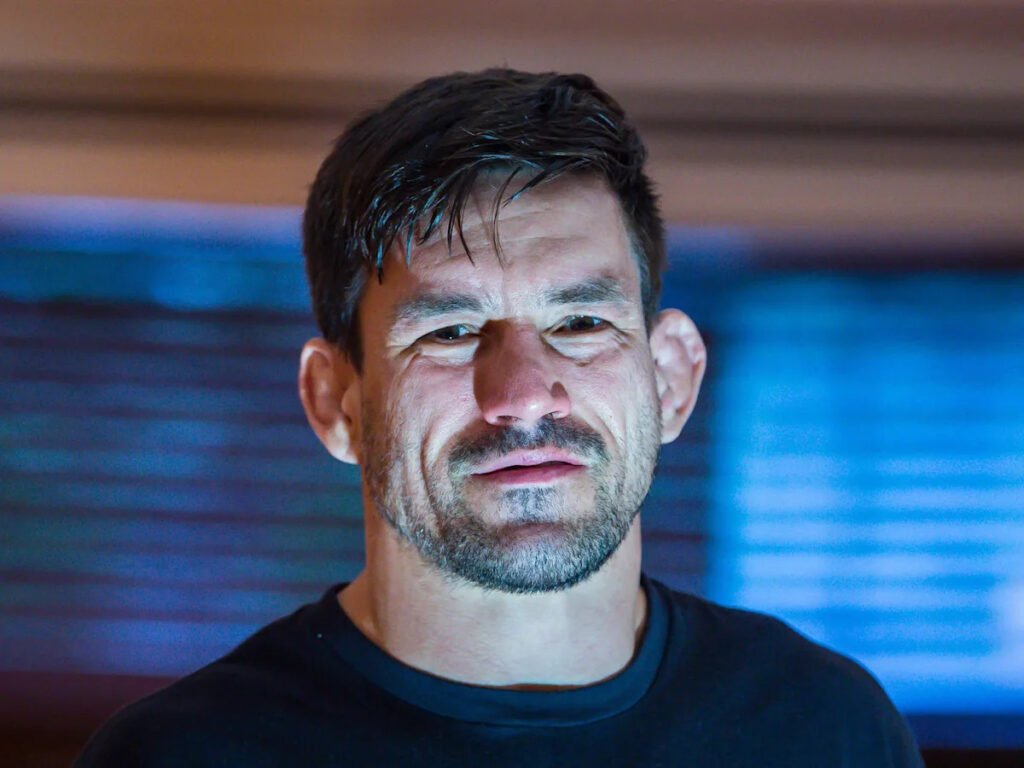

Maia still gets this kind of thing a lot from other fighters. At age 47, he has a few flecks of gray in his beard, but otherwise looks like the same guy we remember from an MMA career that spanned nearly 20 years, almost all of it in the UFC.

These days Maia is mostly a coach and trainer, and his expertise is in high demand. Last Saturday’s UFC Kansas City main event, for instance, was comprised of two guys who both sought out his services. (Garry got there first, so Carlos Prates had to look elsewhere.)

What they come to Maia for isn’t just instruction on jiu-jitsu or submission grappling, though. You can get that lots of places. The MMA world is teeming with black belts, after all.

Advertisement

Maia offers something different. He’s the rare guy who knows exactly how to tailor a jiu-jitsu game for the specific demands of an MMA fight. He knows what works in those cages, with those rules and rounds. He also knows what doesn’t. And he knows because he figured it out himself, the hard way, over the course of many years.

“A lot of people, they think the grappling in MMA is just no-gi jiu-jitsu,” Maia told Uncrowned this week. “It’s not. It’s totally different. I put a lot of effort into trying to be the best grappler of my time, and to try to develop and understand a way of using jiu-jitsu for MMA.”

That, in itself, was a process. When Maia first came to the UFC in 2007, he raged through the middleweight ranks like a wildfire. He won his first five fights, all via submission, beating the likes of Chael Sonnen and Nate Quarry without ever facing much in the way of resistance. He was simply that far ahead of everyone else when it came to the ground game.

Demian Maia (right) has been a big part of Ian Machado Garry’s UFC journey. (Mike Roach/Zuffa LLC)

(Mike Roach via Getty Images)

But as he climbed higher up the division, he discovered the limitations to his style. He suffered a knockout loss against Nate Marquardt in 2009. He had a fairly disastrous title shot against Anderson Silva in 2010. He realized he needed to up his striking game if he was ever going to reach the top, so he dedicated himself to improving his boxing.

Advertisement

“For a long time, I trained just boxing,” Maia said. “That was a mistake. A lot of guys still do this. They train just their striking, and then just their ground game. But in an MMA fight, they are not separate. In MMA, most things happen in the transitions. You have to understand that and work that into your training.”

The fork in the road came after his 2012 decision loss to Chris Weidman. Against a talented wrestler, Maia opted to stand and trade punches for most of the fight. But while his boxing was improved, it wasn’t a real threat in isolation. Weidman easily outpointed him on the feet and went on to fight for — and win — the UFC middleweight title the next year. Maia went back to the drawing board with his team, who hit him with some tough love regarding the necessary course corrections.

“I remember [after the Weidman fight] we were talking about what we needed to change and all that,” Maia’s longtime manager Eduardo Alonso told me in 2019. “At one point, [Maia] said, ‘But I felt like I was right on the verge of knocking him out at any minute.’ We all looked at each other and at him and we had to say, ‘No, that was never close to happening.’ You know, that was the peak of him wanting to be a striker, and he was in that bubble partly for emotional reasons.”

What Maia and his team realized was that, no matter how he improved his striking game, he was never going to be as elite on the feet as he was on the mat. His boxing was a thing that had to exist, but it had to be a means to an end. To the extent that he spent any time striking on the feet with opponents, it needed to be done with the goal of transitioning to the ground, which was where he would really win fights.

Advertisement

“I changed my training then, and my thinking,” Maia said. “I wouldn’t just do boxing; I would do boxing with clinches, with takedowns. I would train with boxers, but I would throw two punches and then look for where I could clinch, where I could take down. In MMA, you need to know where all the opportunities are, not just for you but also your opponent, where he could elbow you or throw a knee. You can’t just do these things separate.”

The result was a late-career renaissance. Maia changed his whole outlook on the sport. He dropped down to welterweight. He won seven straight fights at one point. He submitted guys like Carlos Condit and Matt Brown. He choked decorated wrestlers like Ben Askren. One night he squeezed Rick Story’s face so hard he made blood shoot out of his nose on live television.

Advertisement

Every opponent knew exactly what Maia wanted to do, but he kept doing it anyway. He even earned a UFC title shot in a second division, though he came up short in a decision loss to Tyron Woodley in 2017.

His last fight came in 2021, when he lost a decision to current UFC welterweight champ Belal Muhammad. After that, Maia moved more into a coaching role. He’d always been a teacher of jiu-jitsu — even former opponents like Magny came to his seminars to learn the magic he’d wielded against them, and Maia enthusiastically taught it to them without worrying that they might become future opponents — and so the transition came easily to him.

But beyond his own instruction in the gym, his career in the cage provided a blueprint that other grappling-based fighters like de Ridder still benefit from and attempt to emulate.

“Some of those very creative moments in his game, like when he couldn’t take a guy down so he’d use the half-guard or the deep half, he showed different ways you could make it all work together,” de Ridder said. “I really liked all the stuff that he did and wanted to be like that. He’s not the most physical guy, not the strongest guy, but he could dominate people.”

Advertisement

These days, Maia said, hearing this kind of thing from the younger generation of fighters helps him feel like he hasn’t been forgotten. He may have had to struggle through the wilderness to find a new path to the waterfall, but it was worth it to see others follow him while paying their respects to the man who led the way.

“That makes me very happy when I hear that,” Maia said. “I tried to always be learning and growing. … When I was starting out, I would ask lots of questions of the older guys and they would always help me. I wanted to do that for other guys too.”

These days the UFC has plenty of fighters who would say he has. And he’s not done yet.

#Demian #Maia #continues #influence #generation #UFC #fighters #Ian #Machado #Garry #Reinier #Ridder