NEW ORLEANS — About three inches in diameter, the blue metal pin-back button is still safely kept in the Jacksonville home of Marc Edwards, the treasured item only unearthed for special occasions.

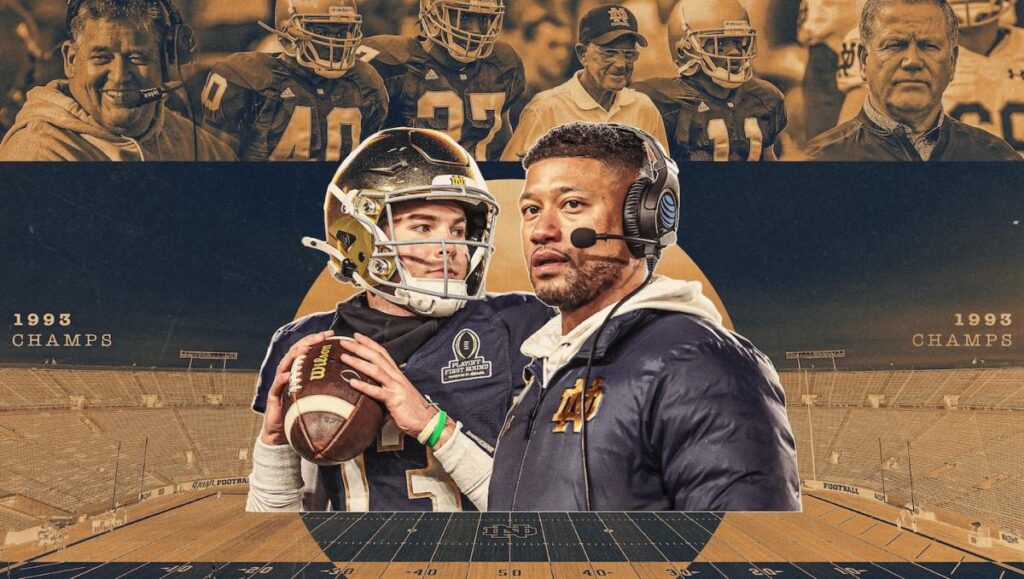

Scrawled around the edges of its face are four words, all in capital letters: NOTRE DAME NATIONAL CHAMPIONS. At its center is a green shamrock emblazoned with the school’s trademark logo — ND — and a year: 1993.

Notre Dame did not win the national title in 1993. But the Irish came close enough that then-coach Lou Holtz distributed the metallic buttons to players following a win in the Cotton Bowl that, they believed, would result in, at the very least, a split national championship with Florida State. The very next day, the Seminoles finished No. 1 in the AP and coaches’ rankings despite losing to the Irish in the regular season.

“I’m still pissed off about that,” bemoaned Edwards, a freshman fullback on that team.

The pin-back button stands as a reminder, not only in the near-miss of winning it all, but in an all-together baffling skid: That 1993 team was the last Notre Dame team to win a major bowl game.

“It’s not like the ’72 Dolphins where you break open the champagne,” said Aaron Taylor, an analyst for CBS and a Notre Dame senior offensive lineman in 1993.

On Wednesday night, within the New Orleans Superdome, the Irish are presented with another opportunity to end the streak. No. 7 seed Notre Dame (12-1) meets No. 2 Georgia (11-2) in a College Football Playoff quarterfinal hosted by the Sugar Bowl.

For many, the streak is quite unbelievable. It spans 31 years, 10 major bowl games, eight different opponents and six Notre Dame head coaches.

The last time Notre Dame won a major bowl, Mariah Carey topped the Billboard charts and Steve Young won his third NFL passing title. No player on the current Notre Dame team was even remotely close to being born. In fact, two players on the current team have fathers who were members of that 1993 team: freshman defensive lineman Bryce Young, the son of former Irish D-lineman Bryant Young; and walk-on linebacker Tommy Powlus, son to current Notre Dame deputy athletic director and ex-Irish quarterback Ron Powlus.

Before leaving for New Orleans, the elder Young informed the younger Young of the streak.

“We talked about it,” Bryce Young said Monday from the Sugar Bowl media day. “It’s crazy how long it’s been.”

For a program of Notre Dame’s stature, it seems unfathomable to go so long without a major bowl victory.

The skid covers the 1995 Orange Bowl, 2006 Sugar Bowl, 2018 Cotton Bowl and 2020 Rose Bowl, as well as the 2012 BCS national championship game, and a whopping five Fiesta Bowl losses. The last of those five came in 2021, Marcus Freeman’s first game as head coach, when the Irish blew a 21-point lead in a two-point loss to Oklahoma State.

The most troubling part for the ND faithful? All but two of the 10 games were lopsided. The losing margin is an average of 19 points.

However, the competition hasn’t been light. Five of the last six losses have come against an SEC power, Clemson or Ohio State.

Next up? Oh, you know, just the SEC champion Georgia Bulldogs who have won two titles in the last three years.

“Hopefully, times are changing and we can cement our roots as one of the nation’s elite,” says Taylor. “That’s what this game is about for me. It’s an opportunity to remove any doubt that Notre Dame is a national power.”

For some, Notre Dame’s positioning as an elite in the college football framework is in doubt. In this new era of athlete compensation, can the Irish continue to compete in a more professionalized and transactional world?

The school’s rigorous academic standards and infrequent transfers may make it more difficult. Perhaps, the program can keep cranking out 10-win seasons, but its failures in the postseason to beat blue-blood programs call into question its position in the college football hierarchy.

The Irish remain perhaps the most polarizing program in the country. The school’s branding and logo is routinely rated among the most valuable in all of college athletics. The only major independent football program, the school exists on an island, with its own lucrative NBC television deal and multi-million dollar apparel partnership with Under Armour.

As an example of Notre Dame’s power within the sport, it is the only school with a seat on the College Football Playoff governing board as one of the 11 voting members. The other 10 are representatives of each FBS conference.

The school seems to be adjusting just fine to the new world.

A story published by Sportico earlier this month revealed that the Irish’s collective, Friends of University of Notre Dame, generated $20.5 million in revenue last year. New athletic director Pete Bevacqua has made clear in public comments that the school will participate fully in the impending revenue-sharing concept, with a majority of the funds going to football.

The school is in the process of building a multi-million dollar, 150,000-square foot football facility, too.

It’s all an effort to remain among the country’s elite as the industry’s only independent. Just one thing is missing: big postseason wins.

Most Notre Dame stakeholders believe the 31-year skid can be explained in a single word: talent.

“You’d be lying to yourself if you didn’t look at the academic standards there and say that doesn’t have an impact,” said former Irish quarterback Brady Quinn, now an analyst for Fox. “The quality of student-athlete you are getting is not the same as everywhere else.”

Quinn was part of two of those 10 major bowl losses.

LSU and Ohio State outscored Notre Dame a combined 75-34 in the Sugar and Fiesta bowls in consecutive seasons under coach Charlie Weis. Before those games, Quinn recalls conversations with Weiss about having to outscore those opponents.

“We knew we couldn’t stop them,” he said. “Now, what Marcus has done with the defense, we’ve got one of the better groups in college football. That wasn’t the case back then.”

The 38-year-old Freeman, a defensive coordinator-turned-head coach, has closed the talent gap with his recruiting, Taylor and Quinn both contend. Notre Dame’s defense is ranked in the top 10 in yardage and scoring for the second consecutive year under Freeman and coordinator Al Golden’s leadership.

Littered with pro prospects and All-Americans, the Irish defensive line resembles those in other major leagues. They are bigger, faster and stronger than Taylor can ever remember.

That’s been the missing piece. On the field before the team’s game against Alabama in the 2012 BCS national championship, he recalls the disparity between the two clubs.

“When Notre Dame was walking down the tunnel and Alabama went by, I think all of us thought, ‘Oh s**t!’” Taylor said.

Notre Dame’s notoriously rigid admissions process — with both high school and transfer prospects — is a long-running issue. Former head coach Brian Kelly shined a light on that upon leaving for LSU three years ago. He became the first Notre Dame coach in 100 years to leave South Bend voluntarily for another college head coaching job.

“Part of the lure of [the LSU] job is there are many more avenues toward [winning a national championship],” Kelly said in 2022. “There are not as many paths at Notre Dame.”

Exhibit A: In a world of frantic player movement, Notre Dame accepts limited transfers who have not graduated from their previous school. The school has signed just one undergraduate transfer in three years.

“We’re bringing in rentals and others are bringing in guys who can be part of the program for several years,” Edwards says. “We needed to expand our horizons a bit to keep up with this era.”

Progress, though, is being made. Without lowering its standards, the university is expected to embrace more transfer movement. And perhaps transfers are not the answer anyhow, says Taylor. Take for instance Kelly’s current team: LSU is 8-4 in his third season and playing in the Texas Bowl while the Irish are in the playoffs in Louisiana.

“Things are really going well for him now in Baton Rouge, right?” Taylor laughs.

Perhaps this Notre Dame team carries with it a good omen, too. Four Notre Dame coaches have won national titles in their third seasons: Holtz (1988), Dan Devine (1977), Ara Parseghian (1966) and Frank Leahy (1943). Freeman is in Year 3.

During media day Monday, he shrugged off the question about the major bowl losing streak. After all, he said, what is truly considered a major bowl?

Over the last three decades, the Irish have beaten plenty of ranked teams, toppled those from the SEC and Big Ten and qualified for the playoffs three times.

“I don’t believe much in a ‘major bowl,’” he said. “I believe in the opportunity to go out there and compete and win with guys that prepare like heck with you. And so that’s the mindset we’ve got to have.”

Meanwhile, back in Jacksonville, Edwards and family will watch his Irish on Wednesday night from his outdoor deck affixed with multiple flat screen televisions. Perhaps he’ll even brandish that blue pin-back button and hope the streak finally ends.

“I don’t feel Georgia is the Georgia of the past where they are completely dominant,” he said. “And Notre Dame isn’t the Notre of the past — we aren’t a step down from the elite teams. We are right there with them.”

|

Notre Dame’s major bowl losing streak |

|

|

Game |

Opponent (score) *playoff game |

|

1994-95 Fiesta Bowl |

Colorado (41-24) |

|

1995 Orange Bowl |

Florida State (31-26) |

|

2000 Fiesta Bowl |

Oregon State (41-9) |

|

2005 Fiesta Bowl |

Ohio State (34-20) |

|

2006 Sugar Bowl |

LSU (41-24) |

|

2012 BCS championship |

Alabama (42-14)* |

|

2015 Fiesta Bowl |

Ohio State (44-28) |

|

2018 Cotton Bowl |

Clemson (30-3)* |

|

2020 Rose Bowl |

Alabama (31-14)* |

|

2021 Fiesta Bowl |

Oklahoma State (37-35) |

#Notre #Dame #team #finally #programs #painful #31year #major #bowl #losing #skid