Every year, my company Emfarsis partners with the Blockchain Game Alliance (BGA) to conduct an industry-wide survey of blockchain gaming professionals. And every year, the overwhelming majority of respondents agree that digital asset ownership is the single biggest benefit that blockchain can bring to games; this year was no different, with 71.1% ranking it number one. Even with more people joining the industry — in 2024 we had three times as many respondents as compared to the inaugural survey in 2021 — it’s always digital asset ownership that comes out as the industry’s undisputed North Star.

But while we hail digital asset ownership as blockchain gaming’s defining feature, most blockchain games today are free-to-play and don’t require asset ownership at all. On top of that, much-hyped promises that rest on the premise of digital asset ownership remain largely unrealized. Apparently, blockchain gaming professionals have found themselves in a curious bind where the best proposition they have for gamers is the same thing they are making excuses for.

Digital asset ownership has always been central to blockchain gaming, offering players true digital property rights to own, trade, and monetize in-game assets in the form of tokens and NFTs. Going back to play-to-earn’s heyday of 2020-21, digital asset ownership was how you could tell the difference between a blockchain game and a traditional game. Early games required players to buy one or more NFTs upfront. But this created a barrier to onboarding, as many couldn’t afford the NFT(s) or simply weren’t enthused about having to buy an asset in a game they didn’t even know they liked yet.

Of course, these NFTs weren’t just any old game assets, they were yield generating. Buying an NFT in a blockchain game was more like investing in a tool that you need to do a job — a job that paid in crypto. Some of the more entrepreneurially-minded NFT owners started renting out their assets to would-be players, in return for a cut of their earnings. It was an amazing demonstration of the kind of decentralized, permissionless innovation that is made possible by blockchain — a community-led workaround that was developed by the players, not the game developers.

Amazing as it was, the rental system which was popular in early blockchain games like Axie Infinity, Pegaxy, CyBall, and others, didn’t actually solve the onboarding problem. The limited availability of assets and high entry costs created a bottleneck, so the rental demand couldn’t be met, thus perpetuating the friction with top-of-the-funnel user acquisition.

By 2022, in an effort to lower barriers and attract a broader audience, blockchain games had started to embrace the free-to-play model instead. With this, blockchain-based features of the game were treated as optional enhancements rather than a prerequisite to play. Players could purchase assets later, or commit time and effort to earn them, but only if they desired. There was no explicit requirement to do so.

The move came at a time when blockchain games were being pressured to focus less on financialization and more on fun. And it was seen as necessary if they wanted to nab a share of the big, juicy $220B traditional gaming market, made up of billions of gamers that were unlikely to install a crypto wallet let alone put up cash for an NFT.

This contradiction — where digital asset ownership is both a defining feature and a significant barrier — reflects the complexities of blockchain gaming’s evolution. On one hand, ownership is what makes blockchain games special; on the other, requiring it deters players. To attract traditional gamers, who lack Web3 familiarity, developers have prioritized accessibility.

Findings from the 2024 BGA State of the Industry Report back this up. When asked about the biggest challenges facing the industry, more than half (53.9%) cited onboarding challenges and poor user experience, while another 33.6% said that blockchain concepts are not fully understood. Thus, without clear, tangible benefits, the effort and cost of becoming a digital asset owner is unjustified. This reveals a major pain point for developers trying to sell noobs on a clunky tech stack that feels more like a chore than a choice, so you can see how they arrived at the decision not to force it.

But this raises the question: How much blockchain can a blockchain game omit, before the blockchain game is no longer a game on the blockchain?

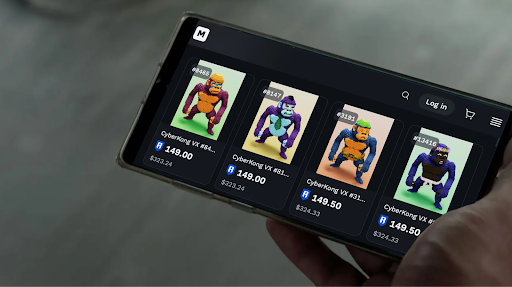

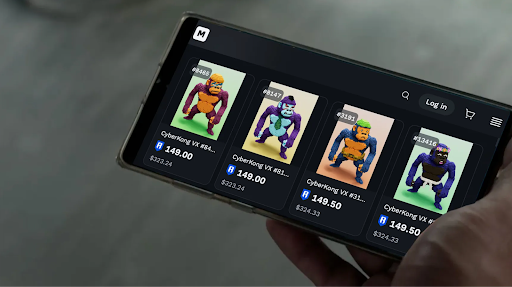

This half-hearted approach to embracing on-chain experiences means that potentially transformative Web3-native innovations — like the promise of interoperability, where players could use a sword from Game A in Game B — remain largely theoretical. Some progress has been made, such as enabling NFT profile picture (PFP) collections to become playable avatars, but this mostly caters to existing web3 communities rather than delivering a palpable benefit to lure the Web2 gaming masses.

True interoperability requires industry-wide collaboration, both technically and economically, which is still fragmented across chains and ecosystems. Meanwhile, developers are sweeping Web3 under the rug, treating it as a layer in the tech stack rather than a defining feature. So for most players, the “Web3” part is hidden, optional, and about as impactful as a collectible spoon in a cereal box.

Frankly, the notion of “ownership” in Web3 is vastly overhyped and largely unsupported by any substantial product-market fit. Web3 ownership, as it’s often sold, is a mirage. The reality is: even if you “own” an NFT, its utility and value often depend entirely on the developers’ centralized infrastructure and ongoing operations. What Web3 does offer is increased agency over your assets, allowing for quicker, frictionless sales. But true ownership? Not so much.

There’s actually little evidence to suggest that Web3 ownership has driven sustainable demand. That said, the ability to exert more control over your digital assets is undeniably valuable — just not the “true ownership” that’s often claimed.

That said, there have been some very promising experiments with fully onchain games and creative catalysts such as the Loot NFT collection. Its composable structure allowed developers to build derivative projects, games, and economies around it without needing approval or input from the original creators.

Other recent innovations born in the arena of digital asset ownership include Ethereum standards ERC-6551, ERC-4337, ERC-404 and soulbound tokens (SBTs). ERC-6551 introduced tokenbound accounts, allowing NFTs to act as their own wallets. ERC-4337 delivered account abstraction, enabling customizable wallets that enhance security and usability without relying on centralized custodians. ERC-404 combined the features of fungible and non-fungible tokens, to offer flexible ownership of both unique and divisible digital assets. SBTs gave us non-transferable, identity-linked assets representing credentials for trust and reputation.

While still early on the adoption curve, these advancements empower gamers to unlock experiences that would never have been possible without digital property rights. And the results of the annual BGA survey confirm that the appeal of digital asset ownership remains strong: it gives players agency, control and value.

The challenge now is to let players experience the fun first and discover the value of ownership organically. But we shouldn’t be ashamed to stand up for what we truly believe in. If we want others to get onboard with our vision, we need to develop experiences that demonstrate the benefits of digital asset ownership from the get-go.

Otherwise, we’re not doing anything very special at all. Are we?

Thanks to Nathan Smale, Duncan Matthes and Owl of Moistness for their review of this article.

#Blockchain #Games #Betrayed #Digital #Property #Rights